A Quantitative Analysis

of the

Effects

of a

Residential Experience

Practitioner Research

Research in Community and Youth Work Module

MA in Community and Youth Work

University of Durham

Peter Stanton, July 2008

Introduction

Those who work with young people have long recognised the value of temporarily removing them from their everyday situations to provide an experience in a new setting where old attitudes and values can be challenged and new experiences can lead to new types of learning.

The 1944 Education Act ushered in an era of state-sponsored residential youth work seeking to promote the personal, social and spiritual development of the nation’s youth. Using a case study approach, this research seeks to quantify the effects of a residential experience by providing a simple measure of the proportion and extent of a group’s perception of its effectiveness.

The background to the research is explored in a chapter that traces the history of residential education with particular emphasis on the British state’s encouragement of the role of the voluntary sector. Research into the effectiveness of residential experiences is introduced and the need for a more cost effective method discussed.

The next chapter introduces the research base for the project, Castlerigg Manor and its examines its methods. In the following chapter, the overall design of the research is outlined before the process followed in the design of questions used in the questionnaire is recounted and examined. A brief account of the sampling process follows.

The chapter on data analysis set out the findings of the research and the means used to derive them. In a chapter entitled ‘Room for Improvement’ the future direction of the research is considered before the main body of the report is concluded.

A number of appendices containing useful information precede the bibliography and some acknowledgements.

Background

The Fruits of War

Much of the modern history of the development of residential experiences grew out of the thinking and concerns of war.

It was in 1861 (and again in ’63 and ’65) during the American Civil War, that Frederick William Gunn walked his students from the Gunnery School for Boys that he had founded in Washington, Connecticut in 1850 the forty miles to Milford Sound to practise camping in order to give them an experience of being soldiers (Smith, 2000-2007). Gunn’s school was ‘based on the belief that strength of character was the goal of education.’ (Gunnery, 2008).

Robert Baden-Powell’s experience in the siege of Mafeking during the Second Boar War taught him much about the strength of character that war could forge in adolescent boys. (Baden-Powell, 1908, Chapter 1). Determined to recreate some of that character building he took a group of 22 teenage boys, from public school and working class backgrounds, away camping to Brownsea Island in 1907 (Smith, 2000-2007).

The Rise of National Socialism in Germany

Scouting was one of many youth organisations that was banned in Hitler’s Germany as the Nazi Party sought to make their youth movement the Hitler-Jugend, Bund deutscher Arbeitjugend the dominant and later compulsory youth organisation in the land (Kater, 2004). Their use of the increasingly militarised movement to disseminate their anti-Semitic ideology and crush dissent has cast a shadow over state involvement in the lives of young people ever since.

The promotion of the kind of character able to resist the rise of National Socialism in the Germany of the 1930’s was a preoccupation of Kurt Hahn, in the years after his rescue from imprisonment by the Nazis in 1934. In Scotland, he re-founded Salem, the school he had established and was forced to abandon in Germany, under the new name Gordonstoun. Hahn’s contribution to character building education was not least in his ability to get things done through his political and establishment connections including Prince Philip who was a student both at Salem and at Gordonstoun. (Warren et al, 1995, p 40)

The Second World War

In the years of the Second World War that followed, Hahn was to continue his innovation of character building activities. In 1941, encouraged and financially supported by Lawrence Holt who had done a study into the causes of death in the war in the Atlantic, Hahn founded Outward Bound in Aberdovey as a short course intended to instil the will to survive in those forced to wait for rescue in the sea after abandoning their vessels (Cook, 1999).

The role that young people would have to play in the Second World War had focused the minds of government, even from the outset. Their moral and physical fitness for war had become an area of concern, as the Board of Education’s Circular to Local Education Authorities for Higher Education No. 1486 testifies:

The social and physical development of boys and girls between the ages of 14 and 20, who have ceased full-time education, has for long been neglected in this country. (Board of Education, 1939)

In the early years of the war, when the outcome was in the balance, the Board set up a committee to address these issues. ‘Character building’ was at the heart of the thinking of this committee whose work lead to the 1944 Education Act. This, essentially conservative, public school-educated group sought to make more generally available the benefits of a public school education. Under the provisions of section seven of the Act, Local Authorities were required to contribute towards children’s ‘spiritual, moral, mental and physical development’ (quoted in Cook, 1999, p 165f).

The Legacy of Peace

Innovation, born out of wartime experience and thinking, had its echoes in more peaceful times. The work of the YMCA in the years following Gunn’s camp in the American Civil War led to regular camps in which both boys and girls came to experience the benefits of the outdoor life. (Smith, 2000-2007)

The massive popularity of scouting amongst boys and girls brought to many in the inter-war period the experience of being away from home to learn new skills and forge new social ties.

With the cessation of hostilities at the end of the Second World War, the concern with ‘character building’ in the public school tradition and ‘fitness for war’ that had inspired the 1944 Act gave way to an emphasis on the social benefits of education. An article advising on the implementation of the Act issued by the Ministry of Education in 1947 in New Secondary Education wrote of the desire that every pupil in a secondary school be encouraged to form ‘sound personal and social relationships with many opportunities for social training arising through residential experiences’. (Cook, 1999, p169)

The Voluntary Sector

During the passage of the Act, several MPs argued strongly that the legislation, while laying a statutory duty on local authorities, should not stifle the pioneering work done by the voluntary sector. This concern found its way into the statute:

A local education authority, in making arrangements for the provision of facilities or the organisation of activities under the powers conferred on them by the last foregoing subsection shall, in particular, have regard to the expediency of co-operating with any voluntary societies or bodies whose objects include the provision of facilities or the organisation of activities of a similar character. (§52 quoted in Cook, 1999, p164)

As a result, Government money was available to fund to all kinds of developments picking up on the ideas of Hahn and the promoters of ‘Outdoor Education’, not least of which were the Outward Bound movement and the Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme (Warren et al., 1995, p 41ff).

The Objectives of the State

In their seminal investigation into youth work in England and Wales, the authors of the Albemarle Report highlighted the value of residential experiences both for social development and increasing the capacity to learn:

Successful association can be furthered by conditions like these. They are not essential to it. The street corner will always have its devotees, and there is a kind of footloose group that deliberately prefers the odd, the heterodox rendezvous to the most civilised amenities. Many groups find their companionship in strenuous physical ventures, in canoeing or cycling together, in camping or travelling across Europe by hired lorry. To be a member of a group, living side by side for a period in camp or on an expedition, can be of special value to social development. Experience of the same kind can be gained from residential courses, which many witnesses have praised for the greater impact they make on young people and the opportunities they give for more stimulating and far reaching work. (Ministry of Education, 1960, §191)

and

With groups like these, association has clearly become more than its own end; it has already become a means of learning, at however humble a level. In any voluntary service of education the social atmosphere must be congenial if there are to be any takers. This applies not only to these informal groups, but it is equally true of the uniformed organisation and the maintained youth centre. It does not only mean that the young will not come if the atmosphere is uncongenial; it means too that the emotional tone of the group has its influence on the process of learning. That is one reason why residential courses, in which a sense of community can be built up over a period of time, are particularly effective in promoting a readiness to learn. (Ministry of Education, 1960, §194)

The potential for the personal and social development of participants in such residential experiences continued the be a theme in government publications through the rest of the century:– the report Effective Youth Work in 1987:

Experiences away from the home and its immediate environment have a rich potential for social learning because, removed from the everyday expectations of the kinds of people they are and the way they will behave, individuals are often able to respond differently and see themselves, and others, in a different light...

Youth workers and young people testify to the value of such residential experiences, and work of lasting significance can sometimes be accomplished in a short time. A period in a residential centre gives youth workers an opportunity to provide both formal settings for learning—such as group discussion and role plays—and informal support to individuals who may be struggling to reach new understandings of themselves and their situation. (Department of Education and Science, 1987 §24, 26)

In the twenty-first century, despite their reinterpretation of the meaning of youth work, the Labour government has continued to stress the importance of ‘residentials’ (as they have come to be known):

Their 2002 blueprint for ‘an excellent youth service’, Transforming Youth Work, speaks of a pledge to young people which involves:

A set of programmes, related to core youth work values and principles, based on a curriculum framework which supports young people’s development in citizenship, the arts, drama, music, sport, international experience and personal and social development, including through residential experiences and peer education. (DfES, 2002)

The 2005 Green Paper Youth Matters. (DfES, 2005) tells of a desire to create a set of national standards that ‘articulate an ambition for the positive activities that all young people would benefit from accessing in their free time’. It goes on to list ‘the full range of exciting and enriching activities in which young people might wish to engage in their free time’ among which is found a paragraph which associates residential opportunities with personal, social and spiritual development and with creativity, innovation and enterprise:

Other constructive activities in clubs, youth groups and classes includes activities in which young people pursue their interests and hobbies; activities contributing to their personal, social and spiritual development; activities encouraging creativity, innovation and enterprise; study support; informal learning; and residential opportunities. §126

More explicit claims for the outcome of summer residential events are made later on in the document which speaks of ‘developing new skills’ by ‘learning through active adventure’ and mixing with others:

In addition, we want to explore the scope for giving more young people the opportunity to take part in summer residential events. Experiences of this sort enable young people to learn through active adventure and to mix with other teenagers from a range of different backgrounds and life experiences. They can also provide a productive context in which to develop new skills, for example, a better understanding of enterprise and business. §142

It would appear that in its modern history, residential education has shown itself to be flexible enough to serve a whole variety of ends that policy makers have sought to achieve through it – from character building, to leadership training (Lee & Yim, 2004), to the establishment of new social relationships, to the promotion of an enterprise culture.

The Effectiveness Question

The literature cited speaks of the value placed upon giving young people experiences of living together away from home, and it also points to some of the supposed effects of such experiences: social development and promotion of a readiness to learn (Albemarle), social learning ... supporting individuals ... reach new understandings of themselves and their situation (Effective Youth Work).

Residential experiences are, however, by their very nature, expensive in terms of the time of skilled personnel and often in terms of travel and accommodation costs. It is not surprising, then, that several studies have been made into the effectiveness of particular residential provisions in achieving these and similar goals:

In 1984, Michael Gass studied the effects on three groups of freshmen of the Wilderness Orientation Program at the University of New Hampshire. Significant effects on retention figures and on grade averages began to be evident two years after the outdoor experience. Developmental behaviours measured using the Student Developmental Task Inventory showed significant positive differences in the task areas of Developing Autonomy, Developing Interpersonal Relationships, Interdependence, Tolerance, and Developing Appropriate Relationships with the Opposite Sex. (Warren et al., 1995, p 365ff.)

Assessing the effectiveness of an experiential learning group for leadership development programme provided by ‘social workers’ to secondary school pupils was the area of interest of Francis Wing-lin Lee and Elice Lai-fong Yim of the University of Hong Kong. The programme involved seven 1.5 hour weekly sessions and a 2-day, 1-night camp. A variety of assessment techniques were employed, including pre-tests and post-tests, group evaluation, worker’s observation and participants interviews. Significant development was found in leadership practice and particularly in self-understanding. (Lee & Yim, 2004)

A Cheaper Alternative

The above studies share several factors in common: they review programmes wherein an appropriate degree of risk was considered essential, they took place over a long time scale with considerable investment of manpower, and importantly, they were investigating activities of high economic value.

In their introduction, Lee & Yim, discuss the effectiveness of a leadership development programme in the context of a competitive environment for schools who need to show they can do more than provide an academic education to their pupils (Lee & Yim, 2004, p 64). The Wilderness Orientation Programs in US universities have to prove their worth in terms of student retention and ‘developmental growth’ (Warren et al., 1995, p 365).

Investigating effectiveness in the provision of residential experiences in the manner of the above studies is beyond the budget of many providers. This research, working within significant constraints of time and budget, seeks to find a lower cost method of assessing the impact of such programmes.

The Research Base: Castlerigg Manor

For practical reasons, this research project has been based at, and investigated the courses provided at the researcher’s place of work, Castlerigg Manor, Keswick.

Castlerigg Manor has been, for 39 years, the residential youth centre of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Lancaster. It’s educational purpose deriving directly from section seven of the 1944 Education Act:

The aim of the Centre is to provide for young people appropriate means of education and training so to encourage the development of their physical, mental, moral and spiritual welfare to full capacity and maturity as persons and members of society better able to meet and improve their conditions of life. (Original Constitution)

Its Educational Method

Proponents of Adventure Education draw strongly on the tradition of Hahn and the Outward Bound Movement he inspired and see risk as an essential aspect of their method:

The initial feeling of uncertainty of outcome is fear of physical and psychological harm. There can be no adventure in Outdoor Pursuits without this fear in the mind of the participant. (Mortlock, 1973 quoted in Hopkins and Putnam, 1993, p 67)

Despite it’s location in the English Lake District, Castlerigg Manor does not provide Adventure Education and does not fall within the remit of the Adventure Activities Licensing Authority set up in the wake of The Activity Centres (Young Persons Safety) Act 1995.

Nevertheless, Castlerigg Manor’s educational method would be instantly recognised by the proponents of Experiential Education, who also look to the tradition of Kurt Hahn. The members of the Association of Experiential Education, too, recognise the importance of having ‘something at stake’:

What I mean by experiential education is a very general belief: that learning will happen more effectively if the learner is as involved as possible, using as many of his faculties as possible, in the learning; and that this involvement is maximised if the student has something that matters to him at stake. (April Crosby, in Warren et al. 1995, p5)

In the Experiential Education method, the student is invited by the teacher to focus on a given problem and to take action to solve it. Although the student is given support and feedback, the possibility of failure remains. The learning cycle is completed with a debriefing in which the learning is articulated. (Laura Joplin in Warren et al. 1995, p 17ff)

Proponents of a theory of Developmental Intentionality (Walker et al., 2005), stress that the educator should concentrate ‘not on shaping youth, but on shaping learning opportunities’ (p 399ff). Whilst criticising them for packing too much into the concept of developmental intentionality, Robert Halpern in his review agrees that:

The adults in a youth program should focus on carefully designing experiences that provide plentiful opportunity for youth to develop the kinds of initiative that Larson describes, rather than trying to directly shape the youth themselves. Such experiences are most engaging when they have, among other attributes, a real-life, hands-on quality (e.g., are naturally complex and messy and have outcomes that are somewhat open-ended); (Halpern, 2006)

Educators at Castlerigg Manor seek to shape learning opportunities for the young people who attend proposing ‘complex and messy’ tasks for students to solve whilst providing a degree of support and feedback and facilitating a debriefing that seeks to highlight the learning experience. The majority of these formal sessions take place with the young people gathered in small groups whose composition remains constant through the course.

It supplements this group work and the formal methods of Experiential Education with more informal approaches where learning is fostered through engagement and conversation.

The Spiritual Dimension

As a centre owned and run by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Lancaster Castlerigg Manor takes seriously its mandate to provide not only for the personal and social development of students, but also for their spiritual development.

In a paper deriving from his doctoral research, Christopher Meehan seeks to create a distinction between ‘spiritual development’ (which he sees as educational in intent and not tied to a particular tradition) and ‘developing spirituality’ (which he defines as catechetical and of a particular tradition) (Meehan, 2002).

To understand the intention of section seven of the Butler Act and the purpose of Castlerigg Manor in the light of that distinction would be to imply that they sought to promote a form of education best suited to the classroom, which would be absurd in the context.

Watson (2000) highlights the fact that individual’s descriptions of spirituality are essentially diverse, because they draw their meaning from different traditions. He argues that in ignoring this, education for spiritual development looses any validity.

Only in developing a particular spirituality can one learn what it is to undergo spiritual development. Just as one cannot learn much of value about poetry without being moved by a poem, it is precisely within religious traditions that spiritual development takes place.

The language of ‘spiritual development’ came into the English language within the Christian tradition and draws on a history of the use of words relating to ‘spirit’ that trace their roots back to the Hebrew scriptures. In the modern, multi-faith context it is usefully applied to many other traditions wherein the initiated seek to grow in understanding and in the ability to live in the light of that tradition.

Attempts to divorce ‘spiritual development’ from any lived tradition run the risk of engendering the kind of frustration that Josef Sudbrack expresses about the word ‘spirituality’ in an article tracing the history of that term:

The banality, however, of the word when one speaks of Christian spirituality and Christian spiritualities, is only the product of our own time, as also is, unfortunately, the anaemic unreality which is almost always connected with the word "spirituality". (Sudbrack, 1975, p 1624)

Within the Catholic tradition, ‘spirituality’ is not a static concept, but is understood to be ‘the personal assimilation of the salvific mission of Christ’ (ibid.). It is developmental in meaning. Spiritual development is about change, about becoming who one is in the light of the Christian mystery.

The Jesuits of Loyola University understand well what constitutes spiritual development in the Catholic context and how to promote it:

Loyola College, as a Catholic, Jesuit institution, offers students many opportunities to explore questions of faith, to develop moral character, to discover and affirm values and beliefs, and to arrive at a deeper understanding of the world and of one’s relationship to God. (Loyola University, 2008)

Spiritual development takes place through exploration and discovery when one encounters others in a community of faith. At the heart of Castlerigg Manor is a community a believers who seek to foster the spiritual development of those who visit through the celebration of the their own faith and an openness to the spiritual journey of others in the context of seeking to address their wider developmental needs.

The Ethics of the Religious Setting

Maxine Green, in her chapter ‘Youth Worker as Converter’ in Ethical Issues in Youth Work (Banks, 1999) discusses what she terms the ‘ethical minefield’ (p 110) of youth workers appointed by religious organisations. Drawing on the National Youth Agency’s definition of the purpose of youth work – ensuring ‘equality of opportunity for all young people to fulfil their potential as empowered individuals’ (p 115) – she seeks to model, in a largely Christian context, what it is to live the values of youth work in the religious setting.

Entries in the Castlerigg Manor web site’s Guest Book make it clear that even a week in a residential setting can greatly influence the lives of the young people. She is right to counsel caution. The Anglican and ecumenical sources (the British Council of Churches – prior to establishment of the Council of Churches for Britain and Ireland with the involvement of the Catholic church in 1990) she cites to argue for open policies that promote ideological maturity would not be considered particularly authoritative in the context of Castlerigg Manor. However, as a Catholic institution, Castlerigg Manor can draw on the church’s Magisterium to guide its policies in a way that does justice to a faith that promotes a God who is prepared even to let evil enter the world to allow room for human freedom (Genesis 3).

In 1965, the fathers of the Second Vatican Council, while restating the right and duty of the church to spread the Gospel, made clear the sensitivity with which that activity must be carried out:

In spreading religious belief and in introducing religious practices everybody must at all times avoid any action which seems to suggest coercion or dishonest or unworthy persuasion especially when dealing with the uneducated or the poor. (Dignitatis Humanae, §4, in Flannery, 1981, p 803)

The Council was not unaware that the overzealous can and have, at times, make a mockery of that teaching:

Although in the life of the people of God in its pilgrimage through the vicissitudes of human history there has at times appeared a form of behaviour which was hardly in keeping with the spirit of the Gospel and was even opposed to it, it has always remained the teaching of the Church that no one is to be coerced into believing. (§12, p809)

A Catholic youth centre must be ever on guard against such a proselytising tendency. To ignore these dangers would not only be to flout the teaching, but would soon become self-defeating: users of the centre are not looking for a more evangelistic approach.

Even though the parties that attend the courses at Castlerigg Manor all come from Catholic schools (where at least the parents of the pupils have opted in) and the pupils themselves are made aware of the nature of the centre when they chose to come on the course, there is still a need for working with caution and sensitivity.

The fact that the participants go to Catholic schools helps to promote this. The Castlerigg staff can be confident that there are others in the lives of the young people who are proclaiming the Gospel, and there are better occasions in the classroom where facts about the faith can be learnt. The aim of the Castlerigg Manor course is not to teach the participants about the faith (although the research indicates that this goes on), but to involve them in the resident community’s celebration of their own faith.

Individuals do ask about the belief systems of the centre’s staff, and it is on this informal level that faith development often takes place.

There is one further safeguard in place to ensure that Castlerigg Manor promotes maturity and not dependence: letting go. The fact that there is no structured follow up from Castlerigg Manor for those who attend courses implies that those who would wish to continue faith development or a deeper involvement in the Church must seek their own opportunities nearer home.

The Particularity of the Context

Castlerigg Manor is one of more than a dozen Catholic youth centres throughout England and Wales (Regan, 2006). Whilst they have no common management and all have their own approaches, there is sufficient common tradition to suggest that the research carried out at Castlerigg could be applied in like manner to the other centres. No doubt, its general nature would enable it to find application outside the Catholic context.

Research Design and Methods

Basic Assumptions

Seeking to determine the proportion of those affected by a residential experience inevitably indicates a quantitative methodology and assumes that what is important about a residential experience can be quantified or usefully measured.

There are, of course, a variety of measurement techniques that could be adopted. It would have been possible to devise all sorts of experiments to quantify such things as a feeling of self esteem, or the depth of a friendship. These had to be ruled out on the grounds of being not only time-consuming, but also exploitative of those who took part.

The use of a questionnaire was chosen as a much simpler and less exploitative method of data collection. The quantitative questionnaire being able to deliver useful data in a form which can be processed in an efficient manner.

Design Constraints

A full assessment of the impact of a Castlerigg Manor course would require a longitudinal study comparing the outcomes of groups of young people who took part in the residential experience with those of there classmates who did not. Such an approach is out of the reach of most centres’ research budgets, and was clearly out of the question for this research project.

The researcher could have adopted a technique such as Winston, Prince and Miller’s (1982) Student Developmental Task Inventory, but the pre-testing and post-testing implied would have been both time-consuming (for participants and for the researcher) and require completion outside the residential context, making it more intrusive and costly.

There was another consideration that influenced the design of the research method. Users of Castlerigg Manor pay for the courses they attend and future bookings rely on meeting the expectations of regular users, hence the level of disruption to their routine had to be kept to a minimum.

On the final day of Castlerigg Manor courses, use is often made of a self completion questionnaire (although in groups not for individuals). This is designed to provide feedback from the young people to help in course evaluation and in the design of future courses. This questionnaire is accepted by regular centre users (school staff) as part of the course, hence the minimally intrusive option for the research project was to substitute a research questionnaire for the evaluation questionnaires currently in use. This had some impact on the course design cycle, but greatly reduced impact on centre users.

The range of ability of the young people who use the centre was also a consideration in research design. A research question that sought to ascertain the proportion of the participants who are affected required a questionnaire that was accessible to a wide range of reading ages. Simple, closed questions were chosen for the questionnaire to even out any bias there might have been in favour of the more articulate.

Question Design

Methodological and Situational Constraints

From the outset, the choice of a quantitative methodology for this research implied that the researcher knew sufficiently what it was that was being investigated. The question being posed was not ‘what are the effects of a residential experience?’ but rather, ‘how marked is this or that given effect?’, ‘how many are affected and to what extent?’ The use of a closed question questionnaire made it all the more important to be clear about the kinds of effects the researcher was hoping to measure.

It didn’t take a the insight of a practitioner-researcher to know that the language of ‘social development’ found in the Albemarle Report and Effective Youth Work was not going to speak to the thirteen to fifteen year olds that would be visiting the centre in the period set aside for the research. The vague and abstract descriptions of development they contained needed to be formulated into simple closed questions that were intelligible to young teenagers.

The stated aims of the course (Appendix 1) could also have been used as the starting point for the design of individual questions, but again the language of that document was designed for staff rather than students. What was needed was a source of language about the experience that was closer to the young people themselves.

A Source of Detail and Language

The obvious source, both of the more detailed recorded effects of a residential course at Castlerigg Manor and of the language necessary to formulate the kinds of questions required, was the archive of the very young people’s evaluations questionnaires that the research would displace.

In recent years a variety of types of evaluation have been employed in connection with Castlerigg Manor courses. Some methods produced ephemeral material (like TV adverts acted out, songs sung and prayers prayed) others more collectable products (like evaluation quizzes and forms). The archive of the latter largely consists of evaluation sheets filled in by the young people in the small groups into which they have been divided during the course.

In the past there has been no systematic policy for the retention of the more permanent of evaluation literature and it appears that often just one of several evaluation sheets has been retained from a given course. The researcher can only speculate as to the selection policies of a succession of course leaders in choosing that one contribution (perhaps the most legible, perhaps what they wanted to hear, perhaps something representative...).

Often the questions posed in the evaluation sheets are designed to gauge young people’s reactions to particular parts of the programme in order to evaluate their effectiveness. So it is only a small proportion of the questions and answers in the archive that are of relevance to assessing the kind of development that a residential course at Castlerigg Manor is apt to engender.

Questions considered relevant to this project were those asking what the young people had learnt and those asking what they would want others to get out of such an experience. (There was a remarkable correlation between the answers to these two types of questions, suggesting that the young people’s expectations of what could be possible from a residential course at Castlerigg was largely defined by their own experience.) In addition, the reasons the young people gave for their characterisation of the quality or value of the course were also of use.

The useful material in the archive of young people’s recorded evaluations from courses goes back some six years to 2002. The collection of relevant questions and answers can be found in anonymised form in Appendix 2 to this report.

Analysis of the Source

Having assembled the material it was then necessary to analyse the types of answers, filtering out those that were not relevant to the research questionnaire, such as reflections on the accommodation and food, on individuals amusing behaviour and comments on particular elements of programmes that were less general in nature.

The types of responses were then be categorised so as to provide some sort of structure and pattern into which similar theme could be grouped.

The following categories emerged in the analysis:

- personal growth

- social development within the group

- attitudes to the world / those outside the group

- religious / spiritual matters

- skills related areas

- fun, laughter and memories

In addition, and not falling neatly into any of the above categories, was a different attitude to family.

Personal Growth

A growth in confidence was often recorded and occasionally the appreciation of the importance of such self-confidence was heightened. Participants wrote of learning about themselves, having a better view of how others see them, valuing themselves more, having more self-belief. They wrote of being more secure, more trusting, being less self-conscious, more open. They wrote of having a sense of achievement, of being changed, of having a new sense of priorities, of being more responsible and a better person.

Social Development within the Group

The young people wrote of learning how to mix, to get on, and make friends, of respecting and valuing others more. They frequently wrote of the joy of making new friends and strengthening pre-existing friendships. They learnt how to be kind and positive to others, to give others a chance. They had a deeper appreciation of the value of socialising. They displayed a deeper understanding of those around them. They wrote of the value of joining in, of trying out new things. Whilst appreciating some of the difficulties of living in community they wrote of a renewed valuing of community life and closeness to others.

Attitudes to the World and those outside the Group

Valuing difference and rejecting prejudice were part of a new attitude the world revealed in their responses. Sessions on world issues encouraged a concern for greater equality in world trade and care for the environment. A more generous attitude and one which does not take things for granted were also in evidence.

Religious or Spiritual Matters

In the Christian setting of Castlerigg Manor, where the participants largely share the Catholic religious tradition of the course hosts, it was not surprising to find in evidence a greater appreciation of both institutional religion and spiritual matters. Along with a greater knowledge, participants wrote of greater faith, of a deeper sense of the importance of church, of finding God (again), of being closer to God, of being more involved in worship, of being more religious and of being less embarrassed about their religion.

Teamwork and a deeper appreciation of the value of it was a strong theme in the evaluations. A greater value on the importance of communication, and of listening was in evidence. Participants wrote of learning to look after themselves, of helping each other, of having better manners. They had improved their skills in decision making, public speaking and in organisation.

Fun, Laughter and Memories

Fun, laughter and the laying down of good memories was an important product of courses. Participants valued new experiences and new-found freedom. It was clear from the analysis that the fun, laughter and memories were highly valued.

Turning the young people’s positive statements about the change that they had undergone into questions enquiring about the presence of those effects (or their opposites) resulted in the generation of fifty-five questions. An additional question about how challenged the young people felt was added to provide some measure of the personal risk the young people were taking.

It became clear when formulating the questions from the above list of effects, that the types of answers fell neatly into one of several ranges:

- the quantitative of extent: much less, less, the same, more, much more

- and: not at all, a little, a lot

- the quantitative of number: none, a few, a lot

- the qualitative: much worse, worse, the same, better, much better.

To increase comprehensibility and to simplify the questionnaire for the users it was decided that questions seeking answers in the same range would be grouped together. This meant that the questions were not entirely thematically grouped.

Constraints of space and of question layout were introduced when aesthetics and the attention span of the intended users of the questionnaire were considered. It was judged that a booklet created from a folded page of A4 paper would be the maximum size and optimum shape for the questionnaire. The minimum point size that maintained an attractive appearance was found to be 10. The font used, Comic Sans MS, was chosen because it is considered easy to read by dyslexic people (Litterick, 2004) and its perceived informality complements the ethos of the establishment.

A desire for clarity and simplicity of layout led to the reduction in the number of questions that appeared on the finished questionnaire with some of the more difficult to understand and the more repetitious of questions removed. (The questions dropped can be found in Appendix 3.) For simplicity it was decided that the consent form should be incorporated into the questionnaire and an initial question asking if the course participants would like to take part in the research was added making the final number of questions 41.

A copy of the questionnaire can be found in Appendix 4 and the accompanying A5 handout produced to explain what the research was about and its voluntary nature, as well as to give some guidance about how to fill it in can be found in Appendix 5.

Anonymity

It was not considered necessary to the research to retain any personal data concerning those who took part. This meant it was simple to maintain a high degree of personal anonymity since there was no place for any name or age or gender to be recorded on the form. The date of the sample, however, was recorded so that school groups could, if they wished, identify their results and different samples be compared for consistency. (Numbers were added to individual questionnaires during the coding process to enable the quality of the data entry process to be monitored.)

The Sampling Process

The Three Samples Taken

Three courses were sampled in the research. The first, ‘Sample A’, on 13th of June 2008, was a group of twenty-six male and twenty female (46 in total) students from year 9 of a large city-centre Catholic secondary school with a sixth-form.

The second, ‘Sample B’, on 20th of June 2008, was a group of forty-six male and seventeen female (63) students from year 9 of a rural Catholic secondary school. (The researcher had only limited contact with this group during the course.)

Sample C, on 11th July 2008, was of nineteen male and thirty female (49) students from year 10 of a small town Catholic secondary school.

The Course Content

All three courses had a similar structure and all parties were accompanied by a mixture of school staff who had attended before and some who were new to Castlerigg Manor. None of the students had previously attended a course (although a couple has visited previously).

Arriving early on Monday evening after orientation sessions for staff and students and a meal, all programmes featured a team-building game (in small groups) and after a break a chance to write up a diary of the day and a short night prayer.

After breakfast, Tuesday began with a series of short, competitive, team-building games and after a break continued with a creative activity. After lunch the parties went for a (two hour) walk in the countryside. Before the evening meal there was a singing practice and a brief time of collective prayer. A simulation game followed (either relating to world trade or to asylum seekers), then ‘diaries’ and night prayer.

Wednesday began with a group-based activity that required the participants to argue a case (for the release of a hostage – A, or for the passage of a law – B & C). A group sharing session followed a break. After another walk in the afternoon there was a group-based performance activity. A reconciliation service formed the night prayer after ‘diaries’.

Thursday morning saw the small groups in three workshops: prayer, affirmations and preparing for mass. The afternoon began with a short walk and some time in Keswick after which there was a short singing practice and the celebration of mass. The evening was taken up with some games, a disco and night prayer.

The Sampling Session

Friday morning began by watching a DVD slide show of the week’s activities. Immediately after that, the researcher addressed the students introducing his research distributing (with the help of school and Castlerigg Manor staff) the explanatory leaflet and then some pens, the questionnaires and a hymn book to rest on while writing.

The students were sat in rows, as they had been to watch the DVD. When they had competed their questionnaires the students could place them in a box. The whole sampling process took between ten and fifteen minutes to complete.

The young people then spent a short while writing up their diaries. After a break and a final prayer they left for home.

Consent

Consent to participation in the research was sought from the organisers of the groups (the school staff) verbally prior to their course at the centre and in writing during the course prior to the question session. Consent forms indicated that the anonymised data would be placed on the web. (Appendix 6)

The young people were also informed that the data would be placed on the world wide web when their consent was sought during the filling in of the questionnaire. (Since the consent question was incorporated into the questionnaire the participants were free at any time before they handed in their completed form to withdraw their consent.)

When the collected questionnaires were examined, there were only two course participants who refused to give their consent to the use of their answers in the research. (Surprisingly, they still filled in the questionnaires, although their answers were ignored.) The two who withheld consent were from the sample where the researcher was not one of the team that delivered the course. Another example of the value of the practioner-researcher’s establishment of a relationship with the researched group.

Data Analysis

Coding and Data Entry

Coding the completed questionnaires was accomplished, adding a number to each answered question equivalent to the count of the number of ticked box from the left of the page. This gave a value of one or two for the first question and answers in the ranges 1 to 3 and 1 to 5 for the other completed questions. Questions uncompleted were coded 0.

The data was entered into a ’.dbf’ format file using a DOS version of dBase (VI). This was the fastest solution to the data entry problem and the resulting tables could be read by a host of other applications including Lotus Approach, Microsoft Access, Clipper and Fox Pro in all their various versions. Additionally, this would mean that the data could be exported in the countless ways that dbf importing software would facilitate.

Software Selection

The desire to give value to the schools that gave consent to partaking in the research led to the promise to participating school groups that the data concerning their group would be made available to them on the web. The Castlerigg Manor website was the obvious way to do this.

To present the data on the site, the researcher chose to use the Perl programming language; a language that is available free on all common computing platforms. Those who programme in Perl – sometimes referred to as Practical Extraction and Report Language, although that is not the origin of the name – can draw on a wide range of software made available in packages for free download on CPAN (Comprehensive Perl Archive Network), including modules for graph production, statistics, statistical correlation and reading XBase files (as dBase files are known). Its value in website production is born out by its extensive use by the BBC.

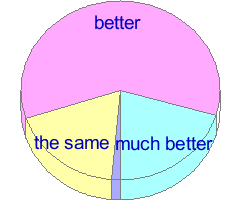

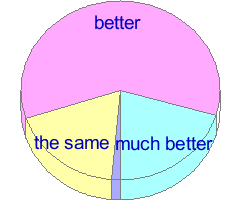

The Perl script developed by the researcher allowed for pie charts of answers to individual questions (for each of the three samples and a per person average), such as the one opposite showing answers to question 6. A comparison of the data produced across the three samples, was also produced to assess the consistency of the results across the three courses.

Positivity in Relation to Questions

In order to provide a figure to express the sampled group’s overall response to a given question a figure called ‘positivity’ was created. This expressed the strength with which the sampled group expressed their opinion in the direction hoped for by the course organisers. The figure being the average of the value generated by a function that translates ‘much better’, ‘a lot’ etc. into the number 2, ‘better’, ‘a little’ etc. into number 1, ‘the same’, ‘not at all’ etc. into 0, ‘worse’ etc. into -1 and ‘much worse’ etc. into -2.; the sense being switched in the case of questions 11, 22, and 29 where the course organisers hoped for answers of ‘much less’.

Thus, if all those who answered question 12 ‘Do you respect others more or less?’ had answered ‘much more’ then the ‘positivity’ rating would be 100%; if all had answered ‘more’ it would have been 50%; if all had answered ‘much less’ it would have been -100%; and if 50% of those who took part said ‘much more’ and 50% said ‘more’ it would be 75% and so on...

Positivity figures were calculated for each question as an overall average and within each sampled group.

Personal Positivity

The same translation function was used to create a figure for the ‘positivity’ of course participants individually, being the average of the function’s product in respect of all the questions answered by that individual. Again, this produced a value that could be (theoretically) in the range -100% to +100%.

Question Groupings

The question design process outlined above threw up a large number of categories into which the questions were divided: personal growth, social development within the group, attitudes to the world / those outside the group, religious / spiritual matters, skills related areas and fun, laughter and memories.

The reduction in the number of questions meant that some of these subject areas were too sparse to yield useful results and it was decided that four categories of question were sufficient: ‘Reactions to the Course’, ‘Personal Development’, ‘Social Development’ and ‘Spiritual Development’. (Appendix 7 lists the division.)

A figure for the average ‘positivity’ of an individual in each of these subject areas was calculated being the product of the above-described function averaged over the questions in the subject area.

Assessing the Overall Positivity of a Group in Relation to a Course

For each of the question categories, graphs of the distribution of the personal positivity figures were produced such as the one on the left showing the distribution of the positivity ratings of all the participants over all question categories.

In addition, graphs of the percentage of course participants who expressed at least a given level of ‘positivity’ for each of the question categories were created. (The one to the right is produced from the same data displayed above.)

To produce a simple figure to express the ‘positivity’ of the group of participants towards the course as a whole and in the four question categories, the area under the curve from 0 to 100% ‘positivity’ was calculated. This was expressed as a percentage of 100% of the participants expressing 100% ‘positivity’. The figure for the above data is 55%.

There was a noticeable difference in the ‘positivity factors’ in the different question categories: Reactions to the Course was consistently high, averaging 85%. Personal Development and Social Development were generally around 50% whilst Spiritual Development was a little lower, averaging 43%.

It was also clear from the plot of the distribution of reactions to questions in the Spiritual Development category that there was a small percentage who considered that they were very negatively affected by the course.

Developmental Impact

A further category of graphs and figures was created being the average of the positivities in the three developmental categories. This figure was denoted ‘developmental impact’. Given the high value for the Reactions to the Course area, this figure came in at a slightly lower 49% for the above data.

This Developmental Impact index represents the simple measure of effectiveness that the research was trying to derive.

The values of this index for the three courses sampled, A, B and C, were 49%, 46% and 51% respectively.

Limitations of and Caveats Concerning this Figure

This figure was certainly produced very simply and it is estimated that the data from another similarly sized course could be processed in less than an hour. However, the simplicity of the process hides a complexity of decisions.

This figure would clearly be different if there were a different set of questions selected. The choice to exclude the chosen question category from this index could be questioned. The figure is calculated with equal bias on each included question. There is a lot of scope for refinement varying the bias to highlight the types of development that would be preferred.

Nonetheless, the question selection process ensured that the questions asked reflected the perceived changes that a Castlerigg Manor course engenders as the high question positivity ratings testify and the measurement is reasonably consistent over the three courses.

A Subjective Measure

It could be argued that since this research is based on young people’s own subjective judgement made at a time of heightened emotion that it has no value and that the lack of before and after testing and the lack of a control group means that it does not really measure development.

These are all important considerations, but the consistency of the answers over the three courses (with single figure standard deviations in the positivity of all questions except question 11) indicate that there is something real being measured and the inverse correlation between the Developmental Impact index and the numbers of young people on the course would tend to support this.

Room for Improvement

Negative Questions

Three of the questions (11, 22 and 29) were asked in such a way that a lower coded response would indicate that the aims of the course were being fulfilled. (E.g. it was hoped by the course organisers that the participants would end up less embarrassed about their religion – question 29.)

Most of those questioned answered accordingly, but there was a significant minority for whom the answers to these questions did not correlate with those given to similar questions. In respect of question 29, thirteen of those who answered appeared to have answered ‘more’ or ‘much more’ when their other answers to questions 23 to 28 would be suggest ‘less’ or ‘much less’ was their real intent. (And there was one person who answered ‘much less’ to all of questions 23 to 29.) As a result the reliability of the answers to these questions is in doubt.

In order to reduce this problem one could introduce more questions in a similar sense so that they would be less of a surprise. Given the range of ability of those who were asked to respond to this self-completion questionnaire it seems likely that this strategy would increase confusion and not produce more reliable data.

Alternatively, one could increase the number of questions so that a similar question in the opposite sense would provide some sort of cover and help to iron out the anomalies. In order to do this with any degree of reliability a much larger number of questions would be needed in both positive and negative senses. This would greatly increase the complexity of the task for the teenagers filling in the questionnaires and increase the processing time of the completed forms. (The judgement of the most experienced youth worker on the Castlerigg staff was that the questionnaire was about as long as it could be and still expect the high response rate hoped for.)

A simpler solution would be to miss out these questions altogether. Although these questions were designed using the language of the target group it is not clear from the responses that all of those who answered knew what ‘self-conscious’ meant or grasped the meaning of ‘taking for granted’. Neither is it clear that the answer to question 29 adds a great deal to the picture. In the research it would produce exactly the same positivity rating as question 28 and would be within 1% of that of question 25 if the nineteen dubious responses were modified by switching their sense.

This solution would leave a questionnaire of entirely positive questions and there would be a risk that the young people would simply go down the form ticking off the same box on each question. Looking at the pattern of answers on the completed forms, this does not generally appear to be the case in those sections where there no negative questions were found. Given the fact that the goal of the exercise was not to find out individual answers of individuals to given questions, but to get a handle on the extent of the impact on the group as a whole, a certain degree of carry over from one answer to another should not unduly affect the final result, just call into question the reliability of conclusions drawn from the data of any given question.

Balanced Questions

Questions 2 to 4 and questions 32 to 41 were not balanced questions. While there is no balance required in question 35 ‘Do you feel you have changed’, some of the questions in this section could have been balanced. The question ‘Have you learnt how to make new friends’ (38) could have been reformulated ‘Do you now know more or less about how to make new friends’, similarly question 33 could have been reformulated ‘Do you value yourself more or less’.

Question Correlation

Bivariate analysis is concerned with the analysis of two variables at a time in order to uncover whether the two variables are related. (Bryman, 2004, p230)

A great deal of time was spent in the pursuit of correlating the answers to various questions, both within the question categories and overall. Graphs and tables of answers given by those who answered a given question in the same way (when there were more than 5%) have been produced for the website. (There is an example in Appendix 8.)

Several suggestions were made for statistical analysis of the relationship between questions.

The data produced by the questions is at least ordinal in that it can be ranked in order (e.g. much less, less, the same, more , much more), but the number of ranks (at maximum five and in question 2 only two were used) make the use of a rank correlation method such as Spearman’s ρ problematic. In such cases useful results can be produced using Pearson’s product moment correlation analysis (Pearson’s ρ in this case since we are dealing with a complete population not just a sample of one) and its square the coefficient of determination (Myers and Well, 2003, p 508).

Coefficients of determination were calculated (on the products of the function used earlier to create values between -2 and +2) for all pairs of questions. The results were not too surprising: There was the strongest correlation amongst questions concerning spiritual development (except question 29). Outside this group only the correlation between questions 30 and 31, between 12, 13 and 17, and between 2 and 4 scored over 30%. There were some more interesting correlations: for instance the correlation between the answers to questions 6 and 27 and between those for questions 24 and 36 (questions in different categories and in different forms) were around 22%.

The usefulness of this question correlation data goes beyond the satisfaction of curiosity: it could be used to refine the questions and help produce a weighting for the calculation of the Developmental Impact Index.

Personal Data

With its intention of assessing the extent of the impact on a course group as a whole, this research project was gender- and age-blind. A different research intent could be pursued by collecting gender, age or other personal data to plot personal positivity within these categories.

Conclusion

The method adopted for this research project has produced consistent results that produce a useful index of the impact of a course with a minimum of disruption to the participants. With the software already written, conducting further sampling would involve little extra research time.

The high take up of the questionnaire provides a high degree of reliability for the data gathered on the distribution of the participants appreciation of the course.

The differences revealed in the appreciation of participants in the area of spiritual development were significant.

This method of analysis can provide useful feedback to supplement the personal appreciation that users of the centre take back to their schools and it could, even in its present form, be usefully applied in similar centres.

Implementing the research has shown up several areas where the process could be improved should future development be feasible and revealed new possible areas of application.

At least in the case of Castlerigg Manor, this research proves that a reliable index of the effectiveness of a residential course can be produced with a low impact on the conduct of the course and on a low budget.

Bibliography

Baden-Powell, Robert S. S. (1908) Scouting for Boys: A handbook for instruction in good citizenship London: Horace Cox.

Banks, Sarah (1999) Ethical Issues in Youth Work London: Routledge

Board of Education (1939) In the Service of Youth, London: HMSO. Available in the informal education archives: http://www.infed.org/archives/gov_uk/circular1486.htm Accessed (10/1/2007)

Bryman, Alan (2004) Social Research Methods Oxford: Oxford University Press

Cook, Lynn (1999) ‘The 1944 Education Act and Outdoor Education: from Policy to Practice’, History of Education, Volume 28, Issue 2, pp 157-172

Crosby, April (1995) ‘A Critical Look: The Philosophical Foundations of Experiential Education’ in Warren et al. (1995)

Department of Education and Science (1987) Effective Youth Work. A report by HM Inspectors. Education Observed 6, London: Department of Education and Science. http://www.infed.org/archives/gov_uk/effective_youth_work.htm Accessed (20/4/2008)

Department for Education and Skills (2002), Transforming Youth Work: Resourcing Excellent Youth Services, London: DfES/Connexions.

Department for Education and Skills (2004), The English Five Year Strategy for Children and Learners, London: DfES.

Department for Education and Skills (2005), Youth Matters, London: DfES.

Flannery, Austin OP (1981) Vatican Council Il: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents Leominster, Herefordshire: Fowler Wright Books Ltd

Gunnery, The (2008) About Us, http://www.gunnery.org/Gunnery/about_gunnery/About_Gunnery/AboutUs.asp Accessed (20/6/2008)

Halpern, Robert (2006) ‘Youth Programs into the Void’ in Social Service Review, March 2006 http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/498839?cookieSet=1 Accessed (20/6/2008)

Hopkins, David and Putnam, Roger (1993) Personal Growth Through Adventure London: David Fulton Publishers

Joplin, Laura (1995) ‘On Defining Experiential Education’ in Warren et al. (1995)

Kater, Michael Hans (2004), Hitler Youth Harvard: Harvard University Press

Loyola University, Maryland (2008) Spiritual Development http://admissions.loyola.edu/admissions/collegelife/spiritualdevelopment.asp Accessed (20/4/2008)

Lee, Francis Wing-lin, and Yim, Elice Lai-fong (2004) ‘Experiential Learning Group for Leadership Development of Young People’ in Groupwork, Volume 14(3), pp 63-90

Litterick, Ian (2003) (Ed. Blumberg, Susan, 2007) General : - an article from dyslexic.com online store PURL: http://www.dyslexic.com/fonts (Accessed 15/04/2008)

Mahoney, Joseph L., Larson, Reed W., and Eccles, Jacquelynne S. (2005) Organized Activities as Contexts of Development: Extracurricular Activities, After-School and Community Programs London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Meehan, Christopher (2002) ‘Catholic Sixth Form Colleges and the Distinctive Aims of Catholic Education in The British Journal of Religious Education Volume 24, Issue 2, Spring 2002 pp 123-139.

Ministry of Education (1960) Youth Service in England and Wales (’The Albemarle Report’) London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office

Mortlock, Colin (1973) Adventure Education Ambleside: (Published privately)

Myers, Jerome L. and Well, Arnold D. (2003) Research Design and Statistical Analysis Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Regan, J. L. K. (2006) ‘Catholic Residential Youth Work’ in Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/Catholic_Residential_Youth_Work (Accessed 21/7/2008)

Smith, Mark K. (2000, 2007) ’summer camps, camp counselors and informal education’, ‘the encyclopedia of informal education’, http://www.infed.org/association/sum-camp.htm. (Last updated: 28 December 2007) Accessed (20/4/2008)

Sudbrack Josef (1975) ‘Spirituality’ in Rahner, Karl (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Theology: the Concise Sacramentum Mundi London: Burns and Oates (pp 1623-1629)

Walker, Joyce, Marczak, Mary, Blyth, Dale and Borden, Lynne (2005) ‘Designing Youth Development Programs: Toward a Theory of Developmental Intentionality’ in Mahoney, Joseph L., Larson, Reed W., and Eccles, Jacquelynne S. (2005) Organized Activities as Contexts of Development: Extracurricular Activities, After-School and Community Programs London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Warren, Karen, Mitchell, Sakofs, and Hunt, Jasper S. Jnr., (Eds.) (1995) The Theory of Experimental Education Boulder Colorado: Association for Experimental Education

Watson, J. (2000) ‘Whose Model of Spirituality Should Be Used in the Spiritual Development of School Children’ in International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, Volume 5, Number 1, June 2000 , pp. 91-101(11)

Winston, R. B., Miller, T. K. and Prince, J.S. (1982) Assessing Student Development Athens, Georgia: Student Development Associates

Acknowledgements

It seems fitting, at the end of this report, to acknowledge my indebtedness to the many people who have enabled me to produce it.

I am particularly grateful for the assistance of my tutor Dr Andrew Orton who suggested more areas for improvement to my work than the constraints of a part time course permitted me to act upon.

I am indebted to the community of Perl programmers, especially Martien Verbruggen and Steve Bonds and all who contributed to the GD::Graph module and Jan Pazdziora for the XBase module.

My thanks go the staff of the schools who permitted me to do this research and to the pupils for their generous response in completing the questionnaires.

And finally I should express my heartfelt thanks to the staff of Castlerigg Manor who have supported me during the whole research process.